Impacts of PFAS on Biosolids Management Costs

By Eric Spargimino, PE, PMP, Environmental Engineer and Regional Team Leader, CDM Smith

In recent years, Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl substance (PFAS) have become a topic of public concern as they are discovered in community drinking water supplies. PFAS have been manufactured and used in various industries around the world since the 1940s, but their enduring prevalence in the environment has raised concerns about the possibility of adverse health impacts. As a result, these concerns have led to many ongoing toxicological studies. The PFAS family constitutes a suite of more than 3,000 known chemical varieties that have been in production and in the environment since the 1940s. Recently, elevated concentrations of these chemicals have been detected in the groundwater in places like near industrial manufacturing sites and especially near airports and military bases where aqueous film forming foams (AFFF) were used.

These synthetic chemical substances are engineered and utilized specifically for their strong carbon-fluorine bonds which are enormously effective at resisting heat, water, and oil. As such, PFAS chemicals are commonly found in everyday consumer products including fast food containers, nonstick cookware, stain resistant coatings, water resistant clothing and personal care products. Due to their chemical structure and their commercial value and use, PFAS are ubiquitous in the environment. They are also persistent, bioaccumulate, and do not readily degrade.

After completing a comprehensive toxicology study, the EPA published perfuorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfuorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) Drinking Water Health Advisories in 2016. Then, in February 2019, the EPA issued its PFAS Action plan. The plan included a goal to move forward with a regulatory determination for PFOA and PFOS. Meanwhile, many states have moved forward with their own limits and regulations, many well below the EPAs 70 ppt health advisory. Many of these limits resulted in biosolids beneficial use programs no longer being able to land-apply their biosolids. This has led to a reversal of all the sustainable and environmentally friendly efforts created by the beneficial use programs. Regulators need to provide their communities the tools they need to limit the release of these substances at their sources, and to educate the public on the impact many of these consumer produce have on the environment.

Evaluating the Impacts of PFAS in Biosolids

In 2004, a national survey of biosolids use and disposal (North East Biosolids & Residuals Association (NEBRA) et al., 2007) found that about 55% of the wastewater solids (sewage sludge) produced in the United States are treated and recycled to soils as biosolids. About 30% of these solids are landfilled and 15% are incinerated. Of the total amount that is beneficially used on soils, three-quarters is applied to agricultural land, 22% is distributed as Class A products, and 3% is used in land reclamation projects.

An evaluation to determine the actual costs to wastewater and biosolids management programs from PFAS was initiated to better understand the potential financial impacts of PFAS to municipal wastewater and biosolids agencies. CDM Smith, in close coordination with the North East Biosolids & Residuals Association (NEBRA), the Water Environment Federation (WEF) and the National Association of Clean Water Agencies (NACWA) led the effort to identify facilities across the country who have been impacted by PFAS and utilized the results from an online survey issued by NEBRA to develop and implement an in-depth survey of the affected facilities. The CDM Smith team contacted impacted parties such as water resources recovery facilities (WRRFs), residuals haulers, biosolids land appliers, and facilities dedicated to end use (incineration, compost, landfill, farms, etc.) and requested detailed information regarding cost and operational impacts from the growing variety of state and federal PFAS policies and regulations.

NEBRA provided CDM Smith with the results of a survey issued to various contacts connected to the association. This electronic survey consisted of 7 questions which included yes or no, open-ended, and multiple-choice questions. While response rates differed depending on the question at hand, NEBRA was able to collect responses from 54 respondents. CDM Smith evaluated the results and used them to aid in the development of the expanded survey. CDM Smith in collaboration with NEBRA, WEF and NACWA compiled a list of potentially impacted facilities that were potential participants for an expanded survey. The team spoke with staff at 28 solids management facilities or operations; the responses were compiled and are presented both qualitatively and quantitatively below. Participants were selected based on their anticipated - and in some cases, already experienced - impacts from PFAS and related policy and regulation. For purposes of this study, the metric used when discussing end use cost was dollar per wet ton ($/wt). This was the unit most commonly used among all those interviewed and is inclusive of the entire product being handled (wastewater sludge or biosolids and the interstitial water).

Quantitative Management Costs

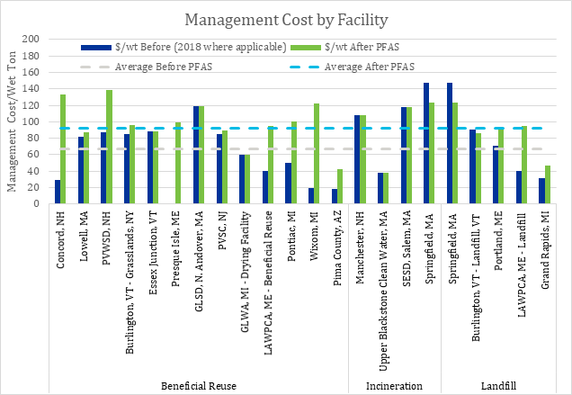

While many of the questions and subsequent responses were more qualitative than quantitative, most of the facilities were able to provide some quantitative management costs pre- and post- PFAS concerns. The cost information allowed for evaluation of the impacts of PFAS regulations on the market so far and aids as a forecast tool for anticipated future costs if regulations proceed as proposed. The management costs provided by survey respondents were converted, for consistency, into terms of cost per wet ton of solids or biosolids leaving the WRRF property (Figure 1). The facilities are broken into groupings based on their management method.

Figure 1. Comparison of biosolids handling costs before and after PFAS concerns by end-use method.

Based on the data provided, the average management cost across the facilities surveyed increased by approximately 72% in response to PFAS regulations. These regulations varied in nature from those directly impacting biosolids, to others regulating ground water and inadvertently impacting biosolids land application programs. Some facilities have seen an increase greater than 300%. Overall, the impact to each facility varies depending on the type of management and geographic location of the facility, among other contributing factors. However, Figure 1 presents clear evidence of significant cost impacts for biosolids management related to the promulgation of PFAS policies and regulations.

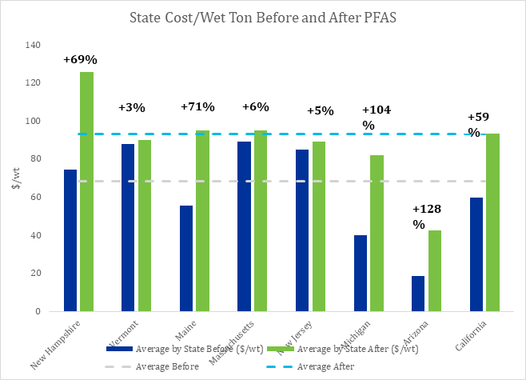

Figure 2 presents the same data from Figure 1 with an emphasis on state-by-state impacts. In grouping the facilities by state, it becomes clear that some states’ PFAS responses have caused significant impacts on solids management costs while others have not.

Figure 2. Comparison of average biosolids handling cost before and after PFAS concerns by state.

Associated Trends

On the federal level, final regulations have not been promulgated for PFAS in biosolids. The state-specific regulations and guidelines that have been proposed or enacted involve various concentration limits of different PFAS compounds in drinking water, groundwater, and in a few cases, surface water. Only Maine has imposed a limit on three PFAS in biosolids, and no state has imposed wastewater effluent standards. Nonetheless, the very low regulatory standards for waters that several states have adopted are causing wastewater and biosolids management programs significant cost impacts.

In the absence of national regulatory standards, individual states are taking action, so the future of PFAS standards is unclear – and varied. WRRFs and biosolids management programs are being forced to take into consideration current and/or anticipated state PFAS regulations which is why some states having already experienced a significant cost impact while others have not. The unintended consequences of proactively addressing PFAS with water quality standard include these increases in wastewater solids management costs. As states continue to set regulatory limits for PFAS, the wastewater and biosolids management markets will continue to assess the risks and liabilities around their programs. Regulating PFAS at stringent levels – even within waters - has consequences and will continue to significantly disrupt markets if WRRFs and other receivers of PFAS aren’t provided additional management, compliance, or treatment options and funding for transitioning to managing materials for PFAS.